The loss of my father lead me on an education journey to South America; it was an experience that affected my personal and professional life thereafter.

I have read that people may react to a family death in unpredictable ways. My reaction resulted in numerous trips to Colombia where I discovered effective, innovative models of education. My focus was to discover ways to “give back” to my roots, and on the flip side, seek resources that could support U.S. programs such as ELL. Being an e-learning educator for over 14 years, I knew there was a pressing need in this sector of education.

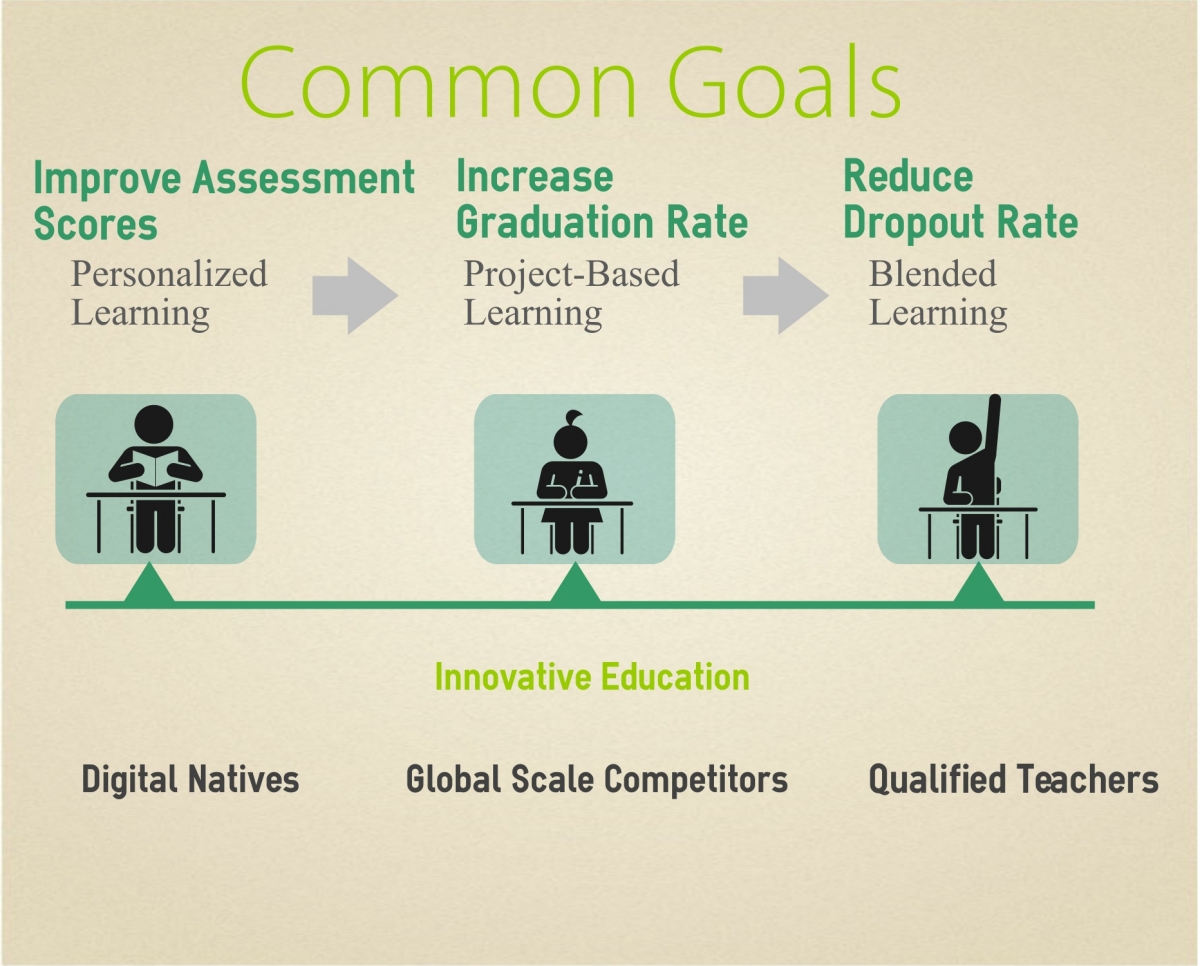

While researching Colombia’s educational landscape I realized that they shared similar issues with the U.S. Their sense of urgency to improve education is based on raising student national assessment scores, keeping up with digital natives, addressing high dropout rates, and preparing students to compete on a global scale.

I have presented at many conferences, using the same slide in every presentation, which outlines a similar list of issues we face in any given school district across the U.S.  Such topics include the need to increase graduation and reduce dropout rates, address fluctuating budgets, find and retain qualified teachers, and keep up with digital natives. When I incorporated this slide in a recent presentation to a Colombian secretary of education, the message was clear that they share our pain points and are seeking ways to innovate in education to address learning needs down to the individual student. As part of this initiative, they are looking to integrate project-based learning, personalize education, and implement blended learning models in their pedagogical practice.

Such topics include the need to increase graduation and reduce dropout rates, address fluctuating budgets, find and retain qualified teachers, and keep up with digital natives. When I incorporated this slide in a recent presentation to a Colombian secretary of education, the message was clear that they share our pain points and are seeking ways to innovate in education to address learning needs down to the individual student. As part of this initiative, they are looking to integrate project-based learning, personalize education, and implement blended learning models in their pedagogical practice.

However, while the needs of Colombia and the U.S. are similar, there are three distinct differences in the education agencies’ responses to implementing innovative educational models: 1) Colombia’s sense of urgency to employ the models; 2) An acknowledgement that they need to improve instruction using technology; and 3) Their immediate allocation of resources and funds for supporting this initiative.

I have worked with numerous districts, schools, and education agencies in the U.S. where similar round-table discussions were had regarding the need to be innovative and to support and advance student-centered learning through personalized, blended, and project-based learning models.

So where are the resources and funds to ensure that these innovations are implemented? There appears to be an understanding that the longer we wait to implement innovation, our students suffer without access to models of instruction supporting their individual learning needs. And yet, the movement toward this shift is stalled. Meanwhile, the majority of our students in the U.S. sit through each classroom trying to absorb the “sage on the stage” mode of instruction that was created over 100 years ago without much change.

We still offer “sit and get” classroom instruction in most U.S. schools, believing that this is the best way to learn, even though students are using technology to learn on their own outside of the classroom. In our age of technology, students are being asked to leave their mobile devices “at the door” so that they can listen to 45 minutes of lecture because there is no need to integrate technology in the classroom. As a parent, I ask, “Is this really the way to prepare my sons for the future? Is this the way to prepare them to compete for jobs when students in other countries have used technology in their classrooms for years?” First and foremost, I am a parent. As an educator, I am always thinking as a parent by asking, “Would I want this for my children?” My parental voice is my compass, my measure when researching and constantly seeking ways to improve education. It is clear that “one size does not fit all”.

So, why don’t we offer these models in most of our classrooms? Is it that we don’t have the same sense of urgency as our Latin neighbors? In Colombia I observed a desire to change and an acceptance that their current instructional model of the “sit and get” was an old way of thinking. Their immediate reaction to accept resources and allocate funds to support change that it is needed to improve education for their students. I met with personnel from Colombian universities who recognize that is change needed to improve instruction and shift instructor mindsets beginning within their teacher education programs. During my visits, It was obvious that there are clear relationships between the offices of the secretary of education (serving k-12 education) and universities. I have observed how they work in partnership training teachers to improve instruction in the classrooms. In Colombia there are open communication channels between K12 and higher education, which strengthens each entity’s abilities to serve students overall.

I recently presented at a conference where my session was called Implementing Blended Learning in the Classroom in the U.S. As a habit, I asked the participants why they chose to attend my session. The answer from every teacher was the same; they had no idea what blended learning was and they were curious to learn more about it. Although I was not completely shocked by the overall response, I was surprised that only one teacher (who was new to the region) had any idea of what personalized and blended learning was.

When I put this same question to Latin American educators, the response was an emphatic “yes” and “we want that”, illustrating the point that they have embraced the offer of resources and support necessary to implement innovative models of education. And, they are ready to take action; there is no need for more discussion, debate, and numerous follow-ups, something I have experienced all too often in the U.S.

Moreover, I noted that Latin American education agencies are eager to advance these best practices in their countries, for within the last year and a half, I have been referred to myriad organizations that share the same vision of transforming K12 education.

Colombia’s ultimate goal is to ensure all students have access to educational models that will effect change and advance student learning. They never mention their concerns about how implementation of these models would adversely affect student performance on national assessments or about the lack of funds and resources to support the programs. We know these issues will arise and need to be addressed, but their top concern seems to be bringing the future of education to their classrooms because the urgency is to improve education for every student.

That being said, I believe we have one of the best public education systems in the world. We are rich with resources and talented, dedicated educators. However, my concern is that we have become complacent in our thinking that because we have the best education system, we do not need to take immediate action in a shift toward implementing student-centered learning models. Perhaps it is that we fear change enough to slow the process of innovation in education. Regardless, one thing is clear: U.S. student performance continues to drop compared to our foreign neighbors.

Clearly, there is much work to be done here, and I am obliged to serve and improve U.S. education by continuing to offer support and services for the advancement of learning for all students as we transition to digital curriculum and technology.