Over the last several years, good news about student literacy trends has been hard to come by. Nevertheless, in this year’s What Kids Are Reading report, the largest annual survey of student reading habits, we find cause for hope when it comes to nonfiction reading—along with some useful insights to help educators encourage reading among their students.

With a dataset of more than 271 million books read by 7.6 million students, the What Kids Are Reading report does not lack for data. Our challenge year after year, rather, is to find the right questions to put to the data. This year we decided to focus our questions on nonfiction, and in the process, we uncovered some surprising findings—including results that align with a changing understanding of the importance of prior knowledge and, as always, some data that suggests a way forward.

Offering Instant Access to Nonfiction

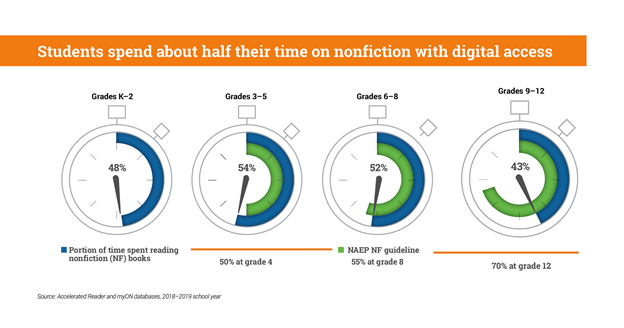

As we dove into the data on nonfiction reading, the most striking outcome we found was the huge difference in student reading practice when nonfiction texts were more easily available to them.

The report’s data comes from myON and Accelerated Reader. With the latter, students sometimes can be limited by what they can physically get their hands on, so the scope of their reading is profoundly impacted by what books are in their school library or classroom. Classrooms, and even many school libraries to some extent, tend to be heavy on fiction. On the other hand, the collections in myON include a large amount of nonfiction.

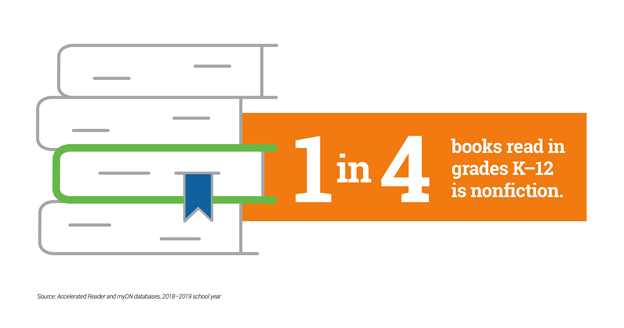

Among the students we tracked through Accelerated Reader, about 25 percent of their reading time was spent on nonfiction. The students using myON, on the other hand, read nonfiction nearly twice as often—students spent nearly half their reading time on nonfiction texts when they were as readily available as fiction. Our data can’t speak to a causative relationship between access and reading habits, but the correlation is undeniable.

The Comprehension Gap Between Fiction and Nonfiction

There’s a prevailing attitude that nonfiction is more difficult for students to comprehend than fiction. When we look at passage rates on quizzes in the two categories, that assumption is borne out—students are more likely to pass a comprehension quiz on a piece of fiction.

The difference is minor, however, with students passing quizzes on fiction 88 percent of the time and only dipping to 83 percent passage on nonfiction. Fiction texts tend to be a little less complex than nonfiction, so this isn’t surprising. We also know that as long as students are above that 80 percent mark, they’re getting optimum growth, so not only are they understanding these books pretty well, they’re getting some effective practice in as they’re reading them.

How to Close it

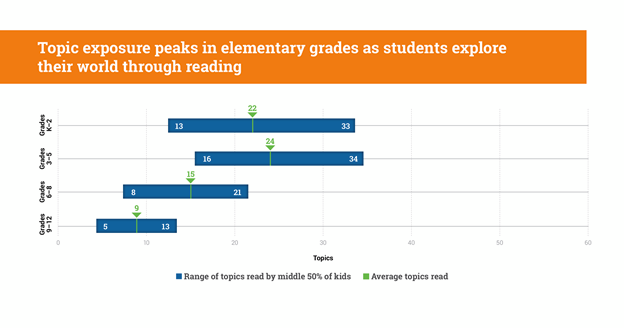

One reason nonfiction comprehension may be so close to fiction comprehension is simply that students are likely choosing nonfiction books on topics they already have a lot of knowledge about.

A series of studies going back to the 1980s has pitted knowledge against reading skills to determine which matters most. A classic study in this vein was published in 1988. "Effect of Prior Knowledge on Good and Poor Readers’ Memory of Text," more commonly referred to as “the baseball study,” divided students into four groups based on high or low knowledge of baseball and high or low reading ability. The researchers then gave the kids a challenging text about baseball, followed by an assessment of their comprehension.

They found that the children with a great deal of prior knowledge about baseball substantially outperformed those with low knowledge, regardless of reading ability.

Another example, from 2014, is "Building Background Knowledge." In this study, researchers again divided students into two groups based on their socio-economic status (SES). They had the students read a text about birds, then assessed their comprehension of what they had read. There was a sizeable gap in performance between the two groups, with the high SES students performing much better.

Next, they gave the students a passage on “wugs,” a fictional animal they made up to ensure that no one could have any prior knowledge of it. When students took assessments of their comprehension of this passage, the performance gaps virtually disappeared. In other words, according to the researchers, the gap in comprehension wasn’t a gap in skills. It was a gap in knowledge.

As E.D. Hirsch says, there is a theoretical difficulty of texts, and there is an actual difficulty of those same texts. The theoretical difficulty is what we can measure with readability formulas. We can measure the vocabulary, the length of sentences—all the various factors used in the variety of formulas out there. But we can’t know the actual difficulty until we place a text in the hands of a reader. If they bring tremendous knowledge of the subject, it will overcome the fact that they might be a struggling reader.

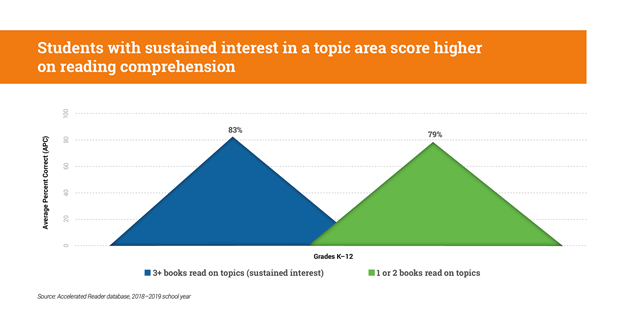

To see if we could find evidence of this phenomenon in our data, we looked for patterns where a student may have dwelt on a topic. We defined “dwelling on a topic” as reading three or more books on a topic or closely related topics. According to the data in this year’s report, when students read fewer than three books on a topic, their comprehension rate was, on average, 79 percent. When they read four or more books, it was 83 percent. Given the size of our data set and the number of kids in there, I would suggest that a four-point spread in comprehension is statistically significant.

Putting the Data to Use in Your School

To help teachers take advantage of the role of prior knowledge in comprehension, this year’s report includes several topics with suggestions for beginning, intermediate and advanced texts on those topics. If a high school teacher is working with her students on the world wars, for example, there’s a page in the report where she can find less challenging texts on the topic for students who have little prior knowledge. She could then offer students with some prior knowledge an intermediate book on the topic, and so on. The hope is that by sequencing the books, we can help students eventually read complex texts on a particular subject.

This data also suggests that, while it’s still a good idea to manage student reading, that management should not be too rigid. If a student wants to read a book more advanced than their theoretical reading ability, rather than telling them “no,” it may be more effective to let them give it a shot or have a conversation with them about their prior knowledge on the subject. Even a struggling reader may be better equipped than anyone else in the school to read a book on a subject they know a lot about.

About the author

Dr. Gene Kerns (@GeneKerns) is the Chief Academic Officer at Renaissance. He is a third-generation educator and has served as a public-school teacher, adjunct faculty member, professional development trainer, district supervisor of academic services, and academic advisor at one of the nation’s top edtech companies. He has trained and consulted internationally and is the co-author of three books. He can be reached at gene.kerns@renaissance.com.