Providing digital equity to every student is much more important than just giving them the ability to complete homework at home. It’s about how to deliver new learning opportunities. Educators have arrived at a crossroads where pedagogy meets network technology. As a school administrator, initiatives that enable high-quality digital learning and provide services and support to instructors for teaching anytime, anywhere on any device, are increasing in importance.

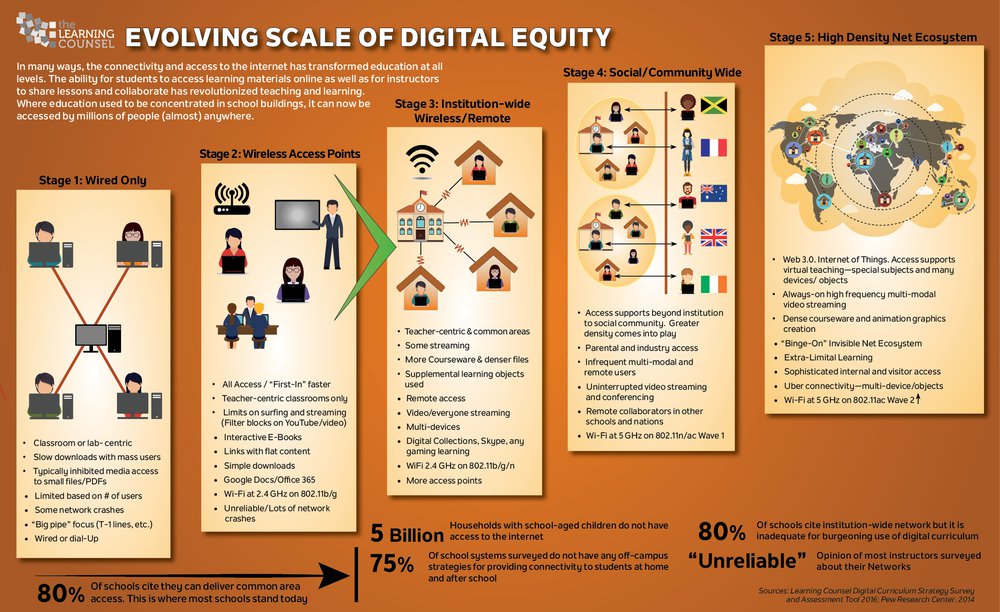

The Learning Counsel 2016 Digital Curriculum Strategy Survey found that even though eighty to ninety percent of schools have network coverage, it’s not enough to support the burgeoning use of digital curriculum. Most educators consider the network to still be “unreliable.” This article and the whitepaper noted at its conclusion, examine how schools are facing the problem of digital equity and explore the main considerations for districts as they make their digital transformation.

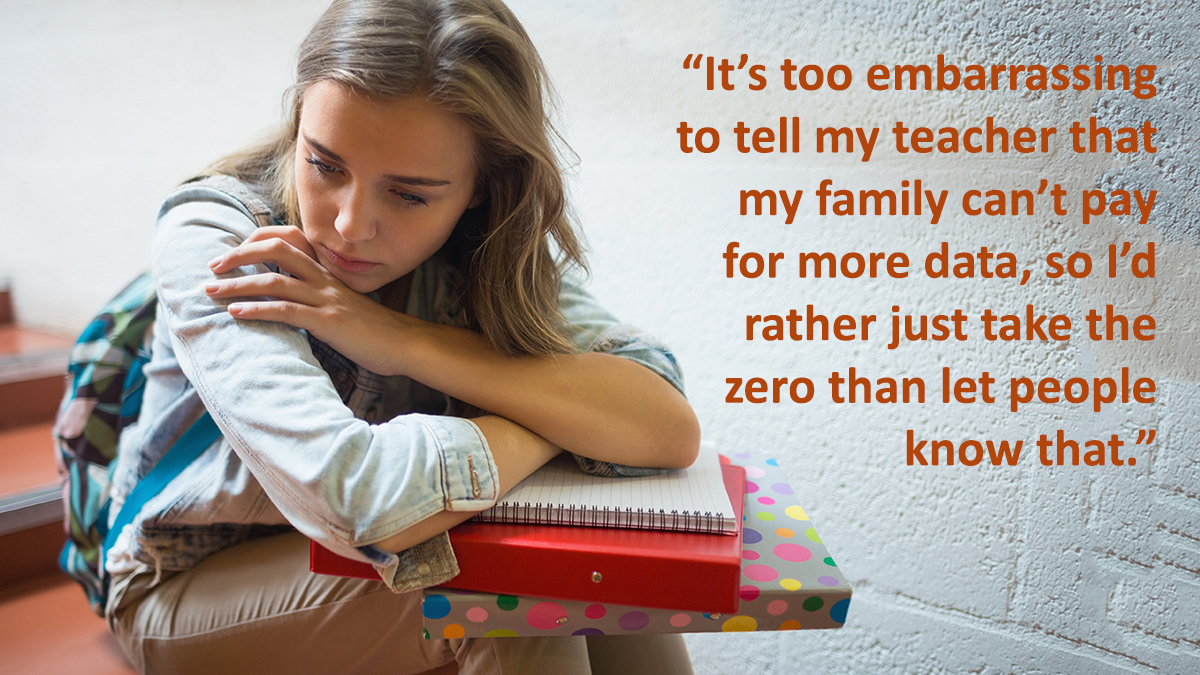

When the bulk of curriculum budget is shifted from paper-based textbooks to digital resources, teachers and schools are running headlong into a new breed of confusion and barriers. Per the Learning Counsel Survey, top issues preventing a thorough transition to digital learning are professional development and technology training, such as building teachers’ professional skills for folding technology into instructional practices.

One of the “fast moving” issues schools are experiencing as they start leaning heavily on digital content, is that most (eighty percent) have not reorganized their budget accordingly. To successfully transition to digital, schools and districts will need to migrate away from paper textbooks as a trade for their digital content and build-out of technology.

Equity is Not Simple

When looking at how schools “go digital,” one of the often-overlooked aspects is the actual digital content. On top of whether the student has a device at all, or whether the network is reliable, is this new equity issue – the richness of the content itself. This new dimension intensifies the most intractable barrier in going digital: disparities based on the class of the courseware or digital objects being offered by the school.

Merely having access (including wired or even dial-up), is no longer enough – the software programming and design of the content is of utmost importance. It must also be delivered seamlessly, without the dreaded buffering symbol forcing students to wait.

If students aren’t able to become actively engaged in their education with tools that are truly digital, not just digitized, they won’t be motivated to learn. Even the most dramatic administrative and operational changes will make little impact if students still perceive the curriculum to be irrelevant, “flat” content that is disconnected from real life. It’s important to remember that the problem with student motivation has two faces: students who are underperforming due to problems posed by their economic situation or language hurdles, and students who aren’t challenged enough or performing ahead of grade-level standards, causing them to suffer through lessons of content they already know.

As software behind digital content becomes increasingly sophisticated, full of clickable links, short and long form video, animated gaming, encouraging screen casting or sharing, and student generated content uploads, with the use of embedded intelligent learning engines, it requires bandwidth that dwarfs simple browsing or PDF downloads. To progress to quality digital learning, next generation education networks must be “systematically implemented.”

A giant step toward digital learning implementations is to put a solid plan in place for network, and especially wireless, infrastructure. For example, high-speed broadband, an essential element of achieving digital transformation, is not a part of many campuses. According to Education Super Highway, in 2015, seventy-seven percent of school districts were meeting the minimum goal of 100 kbps per student, adopted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). While that’s an improvement from the thirty percent of schools that reached the goal in 2013, it still left 21 million students in schools not meeting the FCC minimum. Likewise, Internet connection affordability is showing “significant improvement” according to the latest infrastructure survey from the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN). Almost half (forty-six percent) of respondents reported paying less than $5 per megabit per second (Mbps) per 1,000 students compared to twenty-seven percent in 2014.

Related Article: CTO of Summit Public Schools Shares their Evolution

Just a year later, the stakes are being raised. In late 2016, the State Educational Technology Directors Association (SETDA), the source of the original FCC network guidelines, increased its recommended broadband capacity. To support “student-centered learning,” SETDA advised medium school districts (around 3,000 students) to have at least 1 gigabit per second (Gbps) per 1,000 users for the 2017-2018 school year, and to triple that by 2020-2021.

To exploit high-speed data connectivity, the hardware and software running in the school district data center, onsite at school locations, and within individual classrooms needs to be brought up to par with an eye to future growth. Both the number of devices (2-7 per student) and the “heavy” bandwidth use of immersive digital courseware needs to be accounted for. That includes wireless access points, switches, firewalls, systems management/control components and related gear.

What Inequity Looks Like

The Learning Counsel survey cites that seventy-eight percent of students have access to a device for some significant portion of the school day, either with a full 1:1 (one device for one student), bring-your-own-device, laptop carts or a mix of these. Schools are now finding that “sharing” doesn’t work as well when devices are used between multiple students, or randomly accessed. According to the Consortium for School Networking’s (CoSN) report, fewer than a tenth of school systems reported that all students have access to “non-shared devices at home or in the community.” The first inequity is on campus, and due to the adoption of better learning software, it is driving a new kind of inequity that reflects back on the need to ensure uniform device access and higher bandwidth.

Another type of inequity lies in student’s inability to access the network outside of school. Just forty-two percent of district technology leaders ranked lack of broadband outside of school as a “very high priority.” Two-thirds (sixty-three percent) of respondents have no strategy for providing off-campus connectivity to students. While that is an improvement over previous years, the Learning Counsel survey report noted, “The vast majority of school systems are not yet providing leadership on digital equity.”

However, even where broadband exists, there is an issue of how education is delivered over the Internet, with homework and remedial learning turning entirely digital. A recent study by the FCC examined the state of Internet access nation-wide, and as reported by Ars Technica, “millions are still living life in the slow lane” of at-home Internet service. “While the FCC defines broadband as download speeds of 25Mbps, about 47.5 million home or business Internet connections provided speeds below that threshold,” and many, the article noted, “aren’t anywhere close to modern.”

The whitepaper on how to determine your position on the Scale of Digital Equity, the digital equity infographic and the 11 Insider Tips to Achieve Digital Equity is available here.