The Learning Counsel has updated research on the question “how BIG is” with regards to all things digital curriculum. There are plenty of questions to be answered.

The questions include just what is the definition of digital curriculum; how much spending is being done on digital curriculum, by schools and consumers; and what are the numbers of items considered to be digital curriculum of some sort. The Learning Counsel has done a review of publically available data and proprietary research to come up with some answers.

The definition of digital curriculum is, at present, pretty loose. Please see article on“5 Types of Curriculum Things” as one review of the various digital elements. What really constitutes digital and it being also curriculum will, however, continue indefinitely to be a matter of learned and not-so-learned  opinion. Curriculum designers might argue that the “good stuff” meets some certain conditions and has no instructional design flaws. The digerati among us might argue for game-based software build and interactivity as pre-requisites to being truly digital, versus say, the same-thing-now-digitized like a book made into a PDF. In addition, changes in design to fit touch screens and enhanced dimension of interaction are increasing potentials to have instructional design flaws. One day soon it may be a flaw not to use certain colors or buttons functionality, whereas only about 15 years ago the no-no was building pages that had to scroll instead of jumping to the next page.

opinion. Curriculum designers might argue that the “good stuff” meets some certain conditions and has no instructional design flaws. The digerati among us might argue for game-based software build and interactivity as pre-requisites to being truly digital, versus say, the same-thing-now-digitized like a book made into a PDF. In addition, changes in design to fit touch screens and enhanced dimension of interaction are increasing potentials to have instructional design flaws. One day soon it may be a flaw not to use certain colors or buttons functionality, whereas only about 15 years ago the no-no was building pages that had to scroll instead of jumping to the next page.

In addition, there are always new questions of definition as a field matures. For example: Is a “Lesson Plan” written by any teacher, who may not be a trained instructional designer, considered a genuine piece of digital curriculum just because it's digital? Is any simple game teaching how to say numbers in a foreign language real curriculum or a sort of filler? Who gets to say whether all these new media types are augmentative or supplementary versus core curriculum? The discussions and estimations of what's what are best concluded by instructional design experts, although arguably there are not enough of those individuals to go around. Many vendors have various definitions for their products and services, but for broad understanding across multiple vendors and creators, there is need for a simplistic understanding. Especially for the consumers of things deemed educational.

We expect the continuous refinement of definitions as more curriculum goes all digital. Please also see the article on “We Need New Words”.

SPENDING

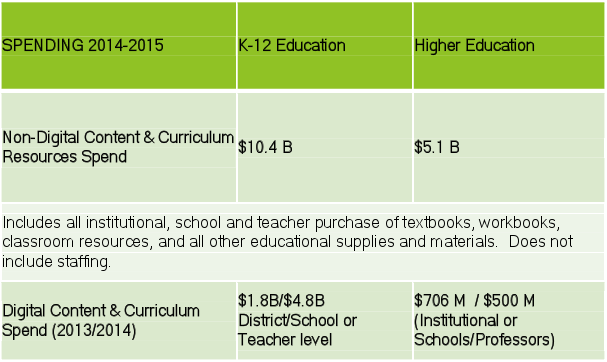

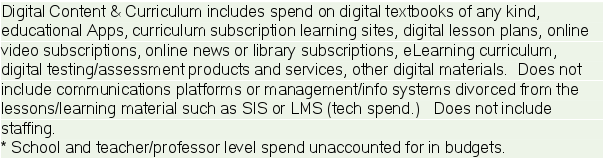

Schools want to know if what they are spending is in line with what others are spending. From a vendor perspective, the question is really “how big is the revenue potential?” The problem with these questions is the fact that most folks are guessing as to total spend by schools. K-12 school budgets may have a line-item, or two, or thirty-five different ones, for curriculum. Just try to figure out most budgets for what's digital curriculum and what's not in all these line items. Then complicate this by the fact that digital curriculum may be being spent out of the IT budgets, or professional development budgets, or some other line item that wouldn't seem likely, and you have the scope of the problem. It's not an easy thing for school administrators to figure out. In addition, spend can be complicated by the fact that some districts provide for individual schools to do a certain amount of spend on their own and do not track individual school budgets. Cross-curriculum programs can spend on their own, even individual teachers on their own. Then you have free content being pulled into individual teacher systems from associations, State repositories, and all sorts of sites that offer freebies.

Reputable Figures

The most reputable figures on curriculum spending are probably the ones from the Association of American Publishers’ school division, although this would not be allthe spending because it's about textbooks. Jay Diskey, Executive Director of the AAP has noted that $8 Billion a year is spent on K-12 textbook (2012.) A number from xPlana in 2012 cited Textbook spend at $7 Billion in 2011.

eLearning for K12 is $2.9B in Sept. 2011 (defined as: “the use of electronic technology to facilitate learning, including computer assisted learning and network enabled technologies.”(Definition from Bromham and Oprandi 2006.) Source: The White House Report on “Unleashing the Potential of Educational Technology,” who cited ”NeXt Knowledge Factbook 2010“, Next Up! Research. This however is really just “tools” and not necessarily the actual curriculum.

In addition, the Center for Digital Education cites the total tech spend at $9.7 Billion in 2013 for K12, explained as the combination of all tech whether for administrative or student computing, inclusive of tech division salaries. This would be separate from Textbook spend, however much of that is “digital” and the White House's citing of $2.9 Billion could be partly inclusive of the Center for Digital Education's number and partly inclusive of the Textbook number. None of those numbers would be inclusive of other curriculum elements such as workbooks, video, subscription services, etc. In addition, those numbers are old or based on the federal base spend data from as long ago as 2010.

The question of “how big” the digital curriculum market is could be the entire potential of the textbook market in K12, growing to usurp much of the regular textbook spend, and also some of the regular hardware/networks/software spend in some budgeting. It could also be usurping parts of other curriculum budgets for, say, professional development, and testing and library/media expenditure.

Many schools have stopped purchasing textbooks entirely in the last three years and have saved up their monies to purchase massive quantities of tablet computers and some digital curriculum. Most of those places have inadequate digital curriculum to replace all they once had with textbooks and workbooks. Las Vegas, for instance, purchased a limited number of five “apps” when they first deployed the initial 7,000-some devices in piloting schools in early 2013. The rest of digital content was to be found via open resources or self-generated by teachers, at least initially.

The Learning Center has determined that the K12 digital curriculum and content market right now is roughly 5.1% of the combined sources of curriculum spend estimated from actual budgets, inventories from several different-sized districts, and review of publisher revenue Base budgets are estimated from the most currentNCES data.

The K12 digital curriculum spend is in the U.S. and rising steeply with the progression of tablet computers.

By 2016 if all schools go 100% digital is potentially some $11.8 Billion, factoring in population growth. This is probably a good number to think with since Pearson, the largest by far with curriculum for K12 is a $9 Billion a year corporation, but their revenues are global though largely U.S. based. They have testing contracts in the $500 Million range in just Texas. CTB/McGraw Hill is a $2 Billion a year corporation. If you take the top five corporations in the market, you probably have a significant portion of the total revenue. The other 770 or so companies scramble for what's left. The thousands of App publishers also make up a sizeable portion of the revenue. Even so, it's easy to picture the actual pie much larger by the sheer figures of the corporations in the K12 education game.

In establishing these numbers, we considered the convoluted workings of school budgets, which distribute funds from the State down to the 13,629 some Districts to some 98,000 schools. A great deal of spend is accounted for in Districts, but individual schools have their own discretionary budgets as well, although these are rarely independently tracked and publically viewable. Add in the 33,000 some private schools and you have a scope that is considerable.

One niggling thought about the burgeoning digital curriculum spend is one of potentially great importance to future school budgeting. It's this: in the past, schools spent on textbooks that were re-usable. Many had a life of 5-7 years. With the advent of digital curriculum, publishers have sought to sell digital versions at a fraction of old costs, but even so schools would have to purchase again with every new user or a per-seat cost. A lot of the re-use is going to be gone, replaced by perplexing questions. Will all the various materials be equivalent to the same sort of historic spend? If a textbook costs $20 per student, but has to be paid for every year, is that the same as a $140 textbook that lasted 7 years? Is the cost to acquire and distribute digitally the same as it was in paper, or are there new risks like lost tablets or codes equivalent to the student's dog eating their textbook? What if the new textbook is not a textbook but some minor percentage of the same knowledge in a new media form? Will other digital materials also have to be bought, or made or found, to make up for the rest of what needs to be learned? What if it's dozens of digital content items to replace what was once a single central thing? Now what happens to actual cost to acquire, vet, organize, maintain and distribute?

The truth is, this fracturing of the textbook centrality of the market is upon us. Schools are already lamenting the fact that their efforts to gather an inventory brings them back lists of enormous size. There are not just individual “things” like textbooks anymore, there are whole subscription libraries of lesson plans, whole suites of curriculum, games, apps, websites to peruse, videos to watch, and more.

The Higher Ed Digital Curriculum Spend

The very nature of the Higher Ed market is towards lots of textbooks, and some digital curriculum. The spending by institutions is not nearly as much as the spending by students on textbooks, which is not accounted for in the total. Much of the digital curriculum is built in-house and is also not accounted for in spend. Many institutions spend on technologies such as lecture capture and digital subscriptions.

How many digital curriculum things are out there?

Millions, perhaps tens of millions. A single Publisher site had 280,000. Websites with some form of curriculum number in the thousands. School and school districts have been building up staggering repositories of their own works. From about 2004-2008 there were unprecedented numbers of scanning bids released by schools. Their work to digitize all their curriculum is still going on.

In the last two years, the leading manufacturers of digital storage have been swept away by the demand coming from what had before been a fairly small market but is now one of their largest.

It is sufficient to say that very few teachers or schools have a good handle on the potentialities. No one does. The days of a School Board or Superintendent making a single multi-million dollar deal for five years’ worth of every textbook, workbook and video needed by their teachers are gone. The entire market is awash with veritable armies of new reps for various types of curriculum, even whilst the open resources movement seeks to bring creditable content in for free.

How much spending is being done by consumers?

One comparison data point is what's happening with apps over all. Spending on the big consumer sites for Apps is not “all” consumer purchasing of educational curriculum type things that might be outside an institution, but it's a large amount of it. Consumers also purchase from folks like Lynda.com , and many others.

According to Juniper Research, “consumers will spend more than $75 billion on mobile applications in 2017.” They credit the surge to the continued growth of the in-app purchase model as well as the emergence of new monetization models for apps.

Juniper predicts that spending on premium app downloads “will generate just 25 percent of total app revenues in 2017, forcing developers to implement business models that leverage in-app virtual goods, mobile advertising partnerships and other alternative revenue streams.”

Juniper also said that “Games will continue to lead all app categories, generating 32 percent of total revenues at the end of the forecast period” and “Increasing tablet penetration also will boost developer fortunes: Tablet owners are set to spend $26.6 billion on apps in 2017, increasing from $7.8 billion this year.”

The fast majority of apps are free, and indications are that consumers, and students, are “increasingly okay with advertising in order to get more apps for free” according to Juniper.

What does this presage for schools? The downloading of apps will be a normal interaction for students, which means that schools will soon be fooling around with delivering apps of their own. The creating of apps, perhaps above many other types of content, will become increasingly interesting to Publishers.

Please also see “Amazon has the most Education Apps”.