Editor’s Note: This is part two in a five-part series

In our first article in this Achieving Equity series, we suggested that the greatest obstacle to equity that students face in the U.S. is their cognitive capacity, because cognitive skills are how students access learning experiences, however they are provided. We talked about the urgency of the situation, especially given the impact of COVID-19 on learning, as well as the impact of poverty on cognitive development. Since education and economics are, essentially, two sides of the same coin, addressing educational equity is essential.

Having identified the problem, we said that we would need to be able to do three things to solve it:

- Understand each student’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses

- Remediate, build and strengthen both weaker cognitive processes and those that are already strong

- Construct learning environments (technology, instruction, curriculum, etc.) incorporating science rather than folklore

In this second article, we discuss how to understand each student’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and their importance.

Cognitive Skills

The term cognitive skills has become much more broadly understood in education over the last decade, but it will still be helpful to be a bit more specific on the kinds of skills we refer to as the foundation for learning. Some of the cognitive skills that matter the most for learning include:

|

Cognitive Skill Category |

Example Skills |

|

Attention |

Sustained Attention Selective Attention |

|

Visual Processing |

Visual Form Consistency Visual Span Visualization |

|

Auditory Processing |

Auditory Discrimination Auditory Sequential Processing |

|

Sensory Integration |

Auditory-Visual Integration Timing and Rhythm |

|

Memory |

Auditory or Visual Short-term Memory Long-Term Memory |

|

Executive Functions |

Working Memory Inhibitory Control Cognitive Flexibility |

|

Logic / Reasoning |

Visual Thinking Conceptual/Abstract Thinking Verbal Reasoning |

|

Higher Order Executive Functions |

Planning Problem-Solving Strategic Thinking |

What can happen when we don’t understand a student’s cognitive profile? Let’s consider the case of Bobby, a real student (but not his real name).

So, What about Bobby?

Bobby is a 10-year old boy who aspires to be an airline pilot. His math grades were good, but he struggled with reading, especially comprehension, which he disliked and had to be pushed to do. When Bobby took a cognitive assessment and we reviewed the results with his parents, Bobby’s spatial perception was at the 91st percentile. His verbal reasoning score was at the 3rd percentile. His other scores were in the expected range. Spatial perception involves perceiving and reasoning with visual-spatial information, being able to manipulate and rotate objects in space and determine how they relate to each other. Verbal reasoning involves understanding relationships, reading between the lines, making predictions and the like, when information is presented in words. It shouldn’t be surprising that a student with low verbal reasoning capacity struggles with reading comprehension. But what if we didn’t have this information about Bobby?

To his teacher, Bobby likely appears lazy or uncooperative when it comes to English Language Arts (ELA) assignments. He appears so bright and capable in so many areas – indeed his scores on all areas of the cognitive assessment were in the middle of the expected range or higher, except verbal reasoning – that it may be very hard for the teacher to imagine why Bobby can’t interpret a text or write more than a couple of basic sentences. At home, Bobby’s mother became quickly frustrated trying to help her son, while his father seemed to have more success. Was this a matter of personalities? Not at all. As we discussed the kind of help Bobby got from each parent, it became clear that mom (an attorney and someone with obviously strong verbal reasoning skills) used her strengths to try to explain material. Dad, on the other hand, who shared strong spatial-reasoning skills with Bobby was more effective because he tended to draw pictures. But each was helping based on their own cognitive strengths, not realizing why one was more effective than the other.

In school, Bobby’s teachers have classes full of students. Some of those students have reading comprehension scores that look a lot like Bobby’s, but that’s really all they can see. Teacher are pushed to get their lagging students up to par to take the annual state assessment. In turn, they urge their students to apply themselves, to work harder, and they give them more of the same kind of practice that failed to help these students succeed the first time. This might be the kind of school that blames the teachers for failing to engage in evidence-based instructional practices. Or it might be the kind of school that calls the parents in and tells them that Bobby is not performing to his potential and that he simply needs to work harder. There are, of course, many other kinds of schools, but those two reactions are very typical.

There is good news in Bobby’s case. Bobby received two things most students don’t get. The first is highly personalized learning strategies that help him use his very strong skills to help him improve his reading comprehension. Creating a Mind Map is one of the learning strategies that helped transform his ability to comprehend the complexities and relationships among ideas in what he read, as well as enabling him to use his visual memory (which was stronger than his verbal memory) to recall the information. True personalization is not just about the “what” (what a student needs to learn), it is about the “how.”

The second was Bobby’s participation in a cognitive training program to build his cognitive capacity. Following 12 weeks of training, Bobby’s score on the verbal reasoning portion of his cognitive test increased from the 3rd percentile to the 46th percentile, from an exceptional weakness to the middle of the expected range.

When students struggle with learning, very often it is not a matter of curriculum or instruction. The underlying reason is more likely a weakness in one or more underlying cognitive skills. In fact, research suggests that more of the variance (42 percent) in academic performance relates to cognitive skills, much more than other factors, including instructional time, instructional quality, and the home environment.

Students from Poverty and Executive Functions

Bobby was one student, but there are times when the underlying reason for learning struggles affects a broad group of students.

In our last article, we talked about the impact of poverty on cognitive skills development. We said, based on a large body of research, that the evidence informs us that economically-disadvantaged students have, on average, less well-developed cognitive skills than their more advantaged peers.

The research suggests that the impact of poverty should be the greatest for the cognitive skills known as executive functions, particularly working memory and inhibitory control. But how big an impact?

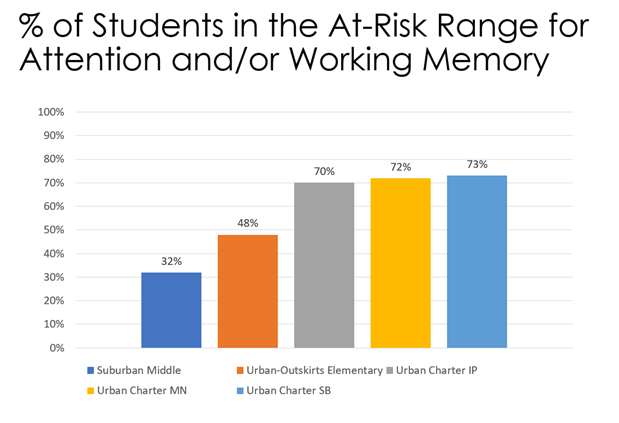

The chart below shows the percentage of students in a variety of schools we have worked with who have significant weaknesses in attention (related to inhibitory control in the assessment given) and/or working memory. A significant weakness here means performance at least one standard deviation below the mean, so the bottom 16 percent of the population, compared to same age and gender peers).

The percentage of students with significantly weak executive functions ranges, for this group of schools, from 32 percent for a comfortably affluent suburban school district to 70 percent or more for several high-poverty urban charter schools. Imagine that you are the teacher for a class of students in one of those charter schools, the majority of whom have poorly developed executive functions.

The first thing that may come to mind is the behavioral problems that are likely to be present in these classrooms. But we need to remember that executive functions are also integral to the learning process. Inhibitory control is what keeps a student from blurting out the first word that comes to mind when decoding a text. In fact, a lack of inhibitory control, based on some research, may be more of a factor than guessing based on context. Working memory is highly correlated with reading comprehension. Working memory is where we hold the information we are reading while we think about it, compare it to what we already know, and give it meaning. These skills are just as important in math (think of how we keep track of where we are in solving a multi-step math problem), and across every aspect of learning.

In these classrooms, personalized strategies can involve grouping of students with similar cognitive weaknesses, but strategies (external prompts to focus attention and instructions given one step at a time) are only part of the story. If we could help students develop these skills, why wouldn’t we?

Coming in part three

The second part of the solution to the issue of equitable access to education based on cognitive development is that we would be able to remediate, build and strengthen both weaker cognitive processes and those that are already strong. That is the part of the solution we will discuss in part 3 of this series.

About the authors

Betsy Hill is President of BrainWare Learning Company, a company that builds learning capacity through the practical application of neuroscience. She is an experienced educator and has studied the connection between neuroscience and education with Dr. Patricia Wolfe (author of Brain Matters) and other experts. She is a former chair of the board of trustees at Chicago State University and teaches strategic thinking in the MBA program at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching and an MBA from Northwestern University.

Roger Stark is Co-founder and CEO of BrainWare Learning Company. For the last decade, Stark championed the effort to bring comprehensive cognitive literacy skills training and cognitive assessment within reach of everyone. It started with a very basic question: What do we know about the brain? From that initial question, he pioneered the effort to build an effective and affordable cognitive literacy skills training tool based on over 50 years of trial & error clinical collaboration. Stark also led the team that developed BrainWare SAFARI, which has become the most researched comprehensive cognitive literacy training tool delivered online in the world.